2023 in the Rearview Mirror

A brief look back on the strategies that led to the year we’ve just experienced in startups

Hi there, it’s Adam. 🤗 Welcome to my weekly newsletter. I started this newsletter to provide a no-bullshit, guided approach to solving some of the hardest problems for people and companies. That includes Growth, Product, company building and parenting while working. Subscribe and never miss an issue. I’ve got a podcast on fatherhood and startups - check out Startup Dad here. Questions about anything? Ask them here.

Note: I’ll be taking some time off for the holidays towards the end of December and first week of January. That probably means fewer newsletters. I hope you survive! I expect to be back in your inbox on January 10. I also hope you survive that.

Question:

“What drove the layoffs, public market flops, and generally crappy year or two that a lot of startups had?”

This question has dominated a lot of conversations this year. Unless you’re a company whose name ends in AI the world hasn’t been kind to you in the past year to eighteen months. And I don’t imagine that we’re quite done yet as we head into 2024. But I’m not in the prediction business (aside from my work with 20VC). I do work closely with and study a lot of companies. And if you’re a fan of this newsletter you know I think about strategy. A lot.

Rather than my Top X Predictions for 2024™ I thought I’d lay out some of the dynamics that I think led to the situation that a lot of startups find themselves in now.

Is this new?

First, let’s establish whether or not this retrenching is new to the startup ecosystem. It is not. Over the last ~decade there was a boom in startup funding. As has been well established this was likely the result of the embrace of the Zero Interest Rate Phenomenon (ZIRP) which continued long-after the financial crises of 2008 and 2020 (remember COVID?).

For an extended period of time it was significantly easier to raise money than it is now. Money was a renewable resource and plowing it into increasingly risky and earlier-stage startups seemed like a great idea. Also plowing more of it into really big startups seemed like a great idea. Profitability be damned! If we just keep growing we’ll figure it out eventually.

For those of you who are old enough to remember the last dot com boom and bust this will not be new to you. Except this time you had SPACs bringing companies to the public markets—who had no business being there—instead of IPOs. And now as private companies lay off people and fold up shop in 2023 at least retail investors aren’t left holding the bag.

Of course, that doesn’t make the layoffs any less painful.

But what did all that money cause companies to do?

There are a handful of broad mistakes that companies made over the last few years because of all that free money; and the chickens came home to roost in 2023.

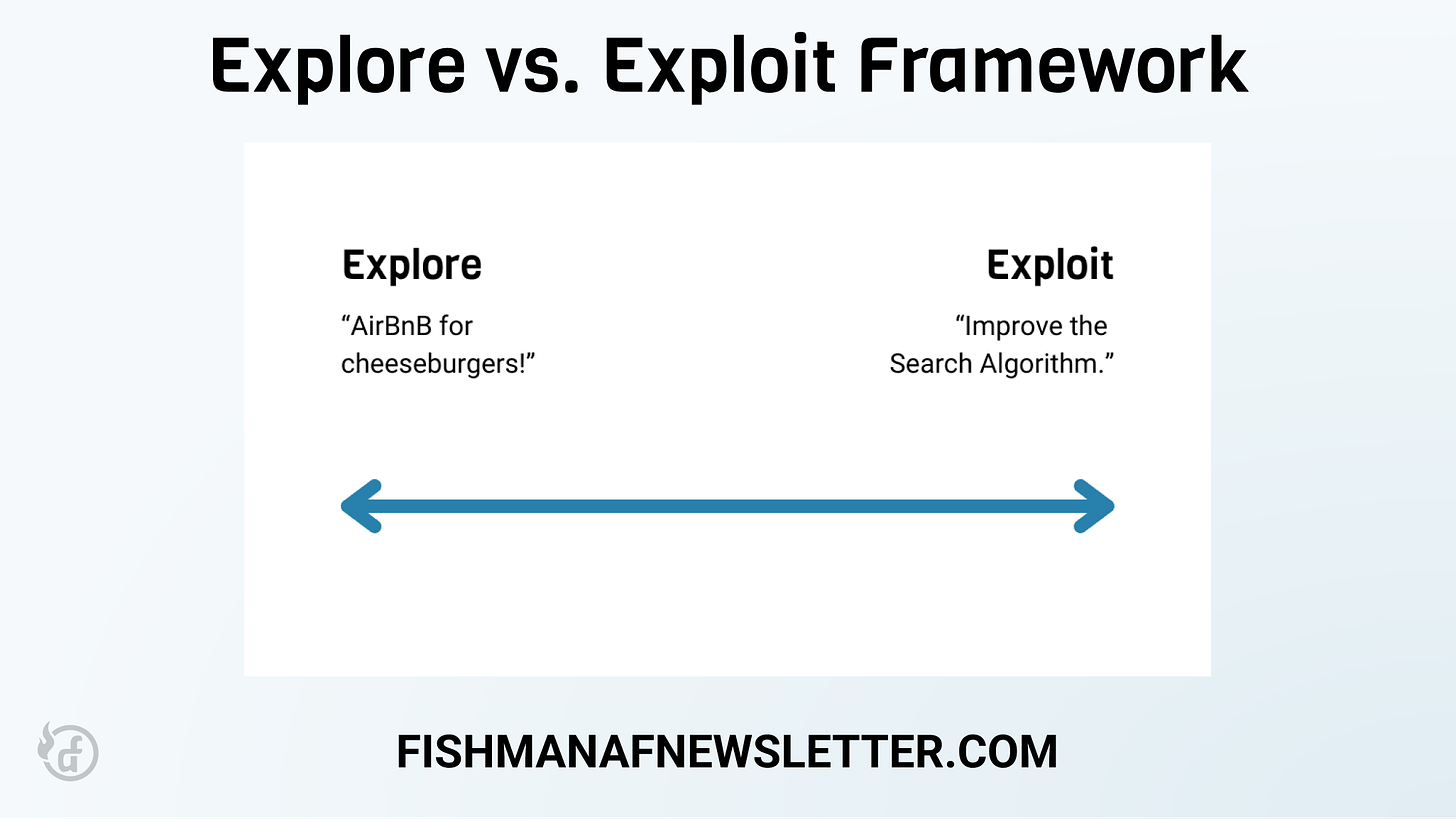

Invert the Explore / Exploit Weighting

One of the company strategy frameworks that I really like is Explore <> Exploit. In this framework a company’s allocation of resources (human, capital, etc.) and focus can be thought of existing on a spectrum between exploiting existing markets, products, and customer profiles and exploring new markets, products, or customers.

Exploiting is less risky because you have a general understanding of the returns. It is also less long-term valuable. Exploring is more risky because building a second product, going into a new market, or targeting a new customer is unproven. You have to establish product/market fit all over again, but if you do then the upside can be tremendous. It’s like building a second company!

The optimal balance of explore vs. exploit will vary depending on a lot of factors—such as where a company is on the product adoption curve, whether it has product/market fit, the pace of innovation in the industry you operate in, and perhaps most importantly: resources.

For those of you who understand gambling, you can think of this as the bets you might make on a craps table. Human nature will demonstrate that the more money you have to bet the more likely you are to make riskier bets with worse odds.

With an influx of relatively cheap capital, and a push for growth at all costs (because capital was cheap and renewable), companies shifted their weighting heavily towards exploration. They then went further overweight towards the scale of that exploration—investing in larger teams much sooner than they might otherwise have on each of these exploration areas.

When the well dried up they had to cut off all of these satellite investments to preserve their capital and that led to ensuing layoffs, trimming product lines, and a renewed focus on profitability.

Lost Sight of Healthy Unit Economics

Somewhat related is that companies lost sight of healthy unit economics along the way. When capital was cheap we didn’t have to do more with less. Instead, we did more with more; or in some cases less with more.

A lot of companies funneled that excess capital into customer acquisition in the form of paid growth. Everyone was complicit in this – from board members all the way down. No sooner had people raised their last round of funding then they were already thinking about the next one. Payback periods got stretched to the breaking point. And then, they broke.

When advertising dollars are growing faster than the number of eyeballs on the largest platforms the efficiency of the ad marketplaces start to kick in. Advertising costs rise in a quest to find that next marginal customer, customer acquisition decreases, and the retained user who had long been ignored is suddenly back in the spotlight; because they churned.

Product/Market Flop

And why did companies fail at retaining those customers?

Two reasons.

First, they never had any business acquiring them in the first place because they weren’t really selling them something that they wanted. I call this Product/Market Flop.

Fueled by outsized fundraising rounds at very early stages companies were able to paper over a lack of product/market fit by buying customers and keeping prices artificially low. Nothing kills a bad product faster than good growth.

Second, because the weight of explore vs. exploit shifted so dramatically building long-term customer retention and satisfaction didn’t matter as much. Existing products and services stagnated. When the initial allure faded or prices normalized, weak customer loyalty churned out people from the exploitable product.

What lessons do we have to learn from this and where do we go from here?

In an effort to rightsize the ship a lot of companies have laid off hundreds or thousands (or tens of thousands) of people over the past 18 months. Fundraising has clamped down, especially at later stages as money is no longer a renewable resource and those Product / Market Flop companies need to re-build a loyal customer base to grow into their outsized valuations.

From a strategic perspective we’ve seen most companies swing the pendulum back to weighting exploit much more heavily than explore. I think for now this is a good thing. At the very least being measured in how many resources they apply to exploration and how many explorations they do.

A lot more companies are starting to take the advice of Chris Zook and James Allen who wrote Profiting from the Core. In their book they argue that the most important thing a company can do is to focus on strengthening its core business. This includes when to expand outward and avoiding too many very differentiated bets.

This means a return to the fundamentals of growth – how to retain customers, how to acquire customers and how to appropriately monetize them.

As to where we go from here entering 2024 I’m excited and hopeful to see a few changes on the horizon:

A renewed focus on building products that people actually want, enjoy and need.

Helping customers build healthy habits with your products.

Lean into more authentic, useful and cost-effective growth loops. You can read about some of my favorites here, here, and here.

Strike the right balance of explore vs. exploit. That doesn’t mean ignore all of the wildly erratic ideas; just most of them.