How to Figure out Metrics Ownership

A Breakdown of the Own - Share - Shed Framework

Hi there, it’s Adam. I started this newsletter to provide a no-bullshit, guided approach to solving some of the hardest problems for people and companies. That includes Growth, Product, company building and parenting while working. Subscribe and never miss an issue. If you’re a parent or parenting-curious I’ve got a podcast on fatherhood and startups - check out Startup Dad. Questions you’d like to see me answer? Ask them here.

I’m back folks! The last few weeks I’ve been away from writing and also largely away from my computer – an extended family vacation to a place with limited/no internet access, then a trip to COVID-town (thanks CrowdStrike + Delta for stranding us in a crowded airport), and then finalizing product strategy with the team at Mozilla (more on that later!). I’ve got a lot of exciting newsletters coming out in the future. Get pumped.

Q: I’m having conflict with some of my counterparts on who is responsible for the different metrics in our user journey. How do I resolve this?

Metrics ownership is a tricky topic. Does the Growth team own that? Does a core product team own that? Who do we point the finger at when it’s not moving in the right direction; who do we celebrate when it is?!? In past articles I’ve highlighted how to get more precise in your identification of metrics, how to set growth strategy, and how to measure and take action with your growth model.

All of that can put you on the right track but when the rubber meets the road and two teams are arguing over the ownership of a metric what do you do?

In this newsletter I’m going to highlight a metric ownership framework that we introduced in the Growth Leadership program at Reforge—something I hope to be able to teach again in the future.

I’ll discuss metric ownership in three steps:

Defining the different ownership types

Mapping ownership to define the ideal breakdown

How to get to your ideal state

Defining Ownership Types

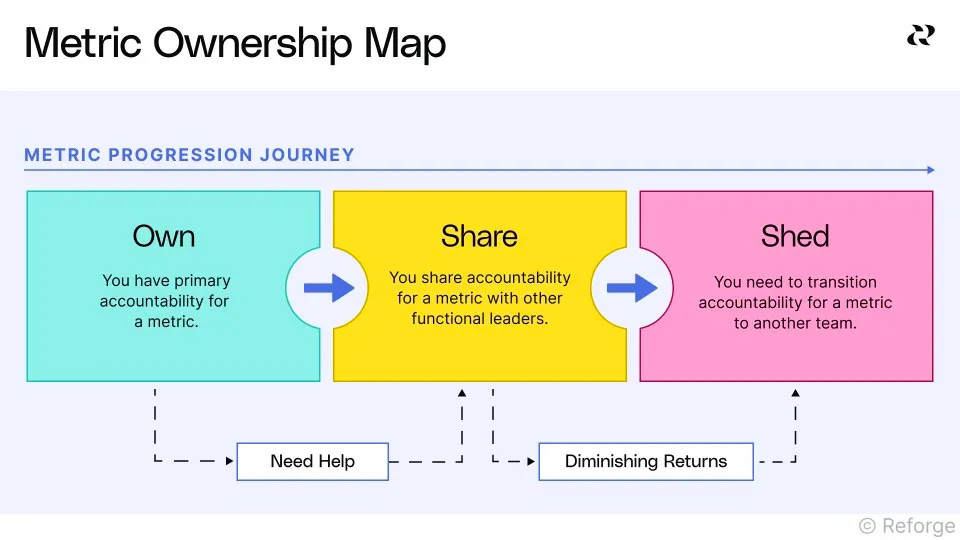

Most, but not all, metrics follow a simple progression: you own accountability for a metric outright, you share that accountability with other leaders and teams, and you hand off (or shed) the accountability to another team.

The first thing to get clear on is the state of the metric and whether it should be in the own, share, or shed state. To do that, we can define some questions you can use to define the state of a metric.

Does anyone own this metric today?

If we were to own it, would we need help to move it?

What does that help look like?

Do other teams have similar objectives with this metric?

What does our impact on this metric look like?

Are we operating our growth team in a centralized or decentralized fashion?

You can run through these questions (keeping in mind you only need to answer the last one once) for each of the important inputs in your growth model. You’ll notice that almost everything I recommend in this newsletter starts with that pesky growth model. So if you haven’t built one yet, even a simple one, then go do that.

Here is how the answers to the above questions change the ownership state.

Does anyone own the metric today and would we need help to move it?

If the answer to ‘does anyone own this today’ is ‘no’ and your growth model identifies it as important then it’s likely that you’ll want to own this metric for now. But the second part of this is that you’ll also need to understand if you have the resources to move it. If you don’t, there’s a case to be made that you should be sharing responsibility with another team. Alternatively, you could advocate to move resources to your team so that you can fully own the metric.

Let’s take an example nested within an activation metric at a productivity tools company (think Notion, Coda, etc.) - inviting team members. In these types of businesses activating a small team into collaborative usage might be more important than an individual.

Chances are that there is a team that works on invites and collaboration. And they own an overall metric on the number of invites sent, number of shared documents, or the rate of invitation. But you, as the Growth Team, are responsible for onboarding success and it’s very important that people collaborate as part of onboarding. This is an opportunity for sharing a metric; or perhaps owning a segmentation of the metric (shared documents in onboarding or within ‘n’ days of signup).

Do other teams have similar objectives with this metric? What does the support to execute against it look like?

Start by looking at whether another team or teams currently owns the metric or product surface area. In our example above, another team focused on invites and collaboration might have overlapping objectives (but in service of a different output). If no other team has similar objectives, you have a strong case for owning it. The second question to ask moves beyond “do we need help” and into “what does that help look like?” In the previous example there is a possibility that you could move a few people temporarily and change from share to own. But if the work and skillset(s) required are significantly different than the capabilities you have on the growth team then you should consider sharing metric accountability here.

What does our impact on this metric look like?

If you own or share a metric and are noticing that your ability to impact the metric is in decline, then it might be time to hand it off to someone else for maintenance. Specifically, you’re looking for a trend in diminishing return—less impact from continued experiments, learning less, or other, more important metrics emerging. The reverse can also be true; if you believe your ability to impact a metric is significantly greater than the team who owns it currently you might make the case that your growth team should own the metric.

Mapping Ownership to Define Ideal State

I don’t want to dance around it: mapping ownership is hard and time consuming. But doing the work now and refreshing during your quarterly or annual planning cycles is well worth it to avoid organizational friction and slowdown.

If you haven’t yet figured out a north star metric or metric constellation then I recommend you pause and read this and this. Okay, thank you. Now we can proceed.

Your North Star metric(s) will be the overarching signal that your product is growing. That’s really great for board presentations, all hands meetings, and investor updates. But to map metrics ownership you need to go levels below the north star into your input metrics.

Input metrics are directly controllable by you (or someone at the company), ladder up to the north star and map to customer behaviors. In an onboarding experience you can think of these as the specific metrics that tell you someone is an activated user, rather than “activation” which is an end goal and too broad for these purposes. It could be: ‘did these 3 actions in the first 5 days’ or ‘invited a collaborator’ or ‘published this page.” All of those are inputs into the number of activated users you have.

Once you’ve mapped those input metrics you need to figure out who (or if anyone) owns them currently. This could be your team, another team, or no one. And you’ll also want to critically evaluate whether that ownership is working. Thanks to perception bias this can become very subjective. People always think the metrics that they own are doing great and the metrics that other people own aren’t. Working with an impartial data person can help you make an objective assessment.

How that you have your metrics, who owns them and an unbiased assessment of how that’s working you can leverage the questions above to determine an ideal state. Run each metric through that series of questions and you’ll end up with metrics, current state and ideal state. This will then point you to which metrics are out of alignment with the necessary ownership state.

Let me give you an example from my time at Imperfect Foods. There was a metric we had called second-order rate. This metric sounds fairly explanatory: the rate at which a customer who places a first order returns to place a second. The growth team definitely had responsibility for some of the success of this metric—setting customer expectations in onboarding on what they would get, what it would cost, and when they would receive it. The better those expectations were set for the first order the higher the likelihood of a second.

However, we weren’t the only team who had significant influence on this metric. Both warehouse operations (packaging and delivery) and to a lesser extent our customer support team also could influence this metric. If a customer received their first order and it was missing a bunch of items or poorly delivered then we had a lower chance of getting them back. If they had an issue and had a poor customer service experience then that further lowered the chances.

So this led us to a share situation where we were jointly responsible for the second order rate and subdivided the metric into mutually exclusive aspects that each team could own.

When you’ve mapped your current and ideal ownership states it’s time to start moving toward the ideal direction.

Getting to Ideal Ownership State

The third big step in the metric ownership process is to get metrics to their ideal ownership state. This doesn’t happen overnight and might take multiple planning cycles throughout the year to get to the right place, but here’s how you get started.

If you believe you or your team should own a metric, which means having total accountability to the outcome, you need both the buy-in from the bosses and the right resources to handle it.

To get buy-in from the bosses I tend to rely on data and experimentation, but your mileage may vary depending on who those bosses are. With data you need to show two things 1) that this is a metric that matters and 2) that it could be even more meaningful with improvements. For experimentation it’s important to show a plan for how you’ll learn, collect data, and the timeline in which you’ll do so. If you need a resource on planning experiments, this is it. The more concrete the better for a leadership team.

The second thing you need to do is figure out your resourcing. In addition to talking about this metric ownership topic, Elena and I cover a staffing framework in Growth Leadership as well. You can check it out here. There are essentially two ways that you can handle resourcing: new hires or borrowing existing teammates. I always recommend starting with “borrowing” and even more so in this financial climate.

If you believe you should share a metric you have to be friendly with the other people in the sandbox to win them over to your cause.

One way that you can do this is through working together on learning and exploration. You can use an experiment brainstorming session, ask for feedback on your hypotheses, and get their help in iterating on that hypothesis. Doing this brings them closer to ownership and starts to make them feel motivated by solving problems that move the metric. I always start by approaching other teams “hat-in-hand” and ask for their advice on the problem, share data, and build some trust.

Resourcing can also be a problem because everyone has other work to do and their first responsibility is to the work that they own outright. Collaborating on the right timelines and expectations, making sure shared metrics are reflected in company-wide objectives (if you use something like OKRs), or even aligning the leaders of the different teams (your boss, their boss, etc.) can help.

If you believe that you need to kick that metric to the curb and it’s time to shed a metric then you have three options:

Put it in ‘maintenance mode.’ This is probably the most common state that a metric can end up in when it’s lived its useful life. It’s important to clearly articulate why having anyone work on improving the metric is no longer important. This could be for many reasons but likely because you’ve exhausted all of your ability to move it and learned as much as possible.

Put on pause. You may have more important metrics to focus on now and can’t find a suitable owner. If this is the case and it doesn’t make sense for anyone to own it then you can clarify that you’ll be pausing work but can monitor for any negative trends.

Give to another team to actively work on. Sometimes it just doesn’t make sense for your expertise and focus. In this case you have to engage in some negotiation and support with the receiving team rather than just dumping it on their lap. If this goes poorly you’ll end up with an important, under-supported metric and no ownership. Help them identify resources, document a clear transition and make sure you continue to help as an “advisor” after they’ve taken it on.

Wrapping it Up

Metrics ownership doesn’t work like Oprah handing out cars.

The best way to handle it is with a three-step process:

Understand your metric ownership types.

Map current metrics and ownership then define an ideal state.

Move to your ideal state via owning the metric, sharing it with another team or teams or shedding it.

The hardest part of this is the third part because that’s when the humans get involved. You can use the gap between current and ideal state—along with why something makes sense in a certain state—to explain and win over stakeholders. Be patient and look for the opportunities that occur throughout the year to make these changes: a planning cycle, a quarterly review, or the annual planning process.

For more detail and a deeper dive on this framework you can check out the Growth Leadership program.