When Branding is a Growth Strategy (Part 1)

How to leverage a brand investment to transform your business OR My story of re-branding Patreon for a customer base more creative than me.

Hi there, it’s Adam. 🤗 Welcome to my weekly newsletter. I started this newsletter to provide a no-bullshit, guided approach to solving some of the hardest problems for people and companies. That includes Growth, Product, company building and parenting while working. Subscribe and never miss an issue. Questions? Ask them here.

Q: How do I know if I’m investing the right amount of time, energy and money into improving our brand? What’s the right balance?

I get this question a lot. Especially from Growth practitioners who aren’t as familiar with brand investments. I was once this person. In fact, I held the belief that brand investment of any kind didn’t matter. My friend Dan Hockenmaier has a nice piece on branding and performance marketing here. The answer to the question above is: invest in improving your brand when your brand perception is getting in the way of growth. In this newsletter that’s exactly what I’ll be writing about.

My opinion on brand investment has changed. And it’s because of my time at Patreon. This is a story of when it was of paramount importance to invest in branding. In fact, without this investment our company would have failed. This was my initiative and the stakes were very high.

This is a two-part article and you’re reading Part 1.

Part 1: Background and steps 1-5 of our ten step process

Positioning statement exercise

Experimentation

Alignment aka the fight for Membership

Personality exercise

The Promise vs. The Proof

Part 2: Steps 5-10 and lessons learned

Building the visual identity and brand guidelines

Eye-popping assets

Firing up the PR machine

Hiding in plain sight

Launch day & Measurement

Introduction

In early 2016 I joined Patreon as the first executive hire outside of the original founding team. I was the 50th employee.

My job: Growth.

I was there to lead the Growth Marketing and Product Growth teams.

For us, Growth was about acquiring creators. Patreon was one of the earliest of the “creator economy” startups and is still (despite a recent takedown article in The Information) one of the few behemoths in that industry. When last reported, Patreon paid out $1.5-2 billion per year to creators via direct membership from fans (or patrons). In comparison, the entirety of federal, state and local funding for “the arts” in FY2022 was $1.85 billion.

When I arrived at Patreon we had impressive user generated content (UGC) and word of mouth growth (WoM) loops, but… our growth was slowing.

We had gone through a massive cleanup phase of the product experience which skyrocketed NPS and reduced monthly creator churn to under 0.5%. This is a staggering metric. That means if we launched 100 creators in Month 1 by the end of month 12 (one year later) we still had 94 of them processing money on the platform. What’s more, each cohort would ~2x its earnings in a 1 year period. Net dollar retention was well north of 100. And still, our growth was slowing.

What we were observing was that creators kept launching, but it seemed as if their earnings were capped. We weren’t seeing the type of high-value creator launch on the platform.

We commissioned a comprehensive research project to understand why. Thinking that maybe we needed to build more vertical specific features for musicians, podcasters, YouTubers, etc. It was called Project Patronaut. What we found was eye-opening and existentially scary for the company.

The problem was not the efficacy of our growth loops or lack of certain features; it was actually the perception of the brand. We were starting to lose the product-market fit we had achieved since launch. Why?!?

When the company launched in 2013 we had anchored ourselves to Kickstarter—a company many creators were familiar with but one that was losing its luster; especially amongst the A-list creator set in early 2016. Kickstarter had stopped growing entirely on a year-over-year basis and what we heard in our research study was “I don’t want to associate myself with crowdfunding. I don’t want to ask my fans for money.” We weren’t doing ourselves any favors here—when I joined Patreon we had a video on the homepage that talked about us as “Recurring Kickstarter.”

This was problematic for us because the larger the creator who launched on Patreon the bigger the impact to the UGC and WoM loops. In other words: large, recognizable creators attracted lots of other large, recognizable creators to the platform. And those large, recognizable creators weren’t launching because, in the paraphrased words of Patreon co-founder and CEO Jack Conte: “Creators want to feel like they’re hot shit. Launching on Patreon felt like you were begging for money.”

We didn’t intend for this to happen, but when your growth is influenced by what other users say about your platform then you run the risk of losing your message. And in 2016 we were starting to. If we didn’t act, the company might cease to exist.

We needed to change perception in a big way… but how do you do that when you can’t convince the type of creators you need on the platform to spin the UGC and WoM loops?!?

I’ve always been more science than art, more quantitative and experimental than qualitative and intuitive. So when I sat in a room with Jack Conte and the rest of the executive team—and we came to the conclusion that we needed to rebrand and reposition the company—I had no idea what to do.

The good, bad, thing was neither did anyone else.

We knew that we needed to change. We needed to drop the crowdfunding perception and reignite interest amongst the “hot shit” creators. The problem was that we didn’t know what we needed to change to.

What we did

In short, we changed everything. The positioning, the personality, and the product features. It wasn’t a pivot, but we repackaged what we offered and how we talked about it. And it worked. Rebranding and repositioning Patreon was the catalyst to 10x-ing the business over the next several years, watching our first creators earn over $100,000/month on the platform and millions per year, and leapfrogging competition that didn’t know what to do when they heard “we don’t want to ask our fans for money.”

From the middle of 2016 to the middle of 2017 (June 14, 2017) I took the company through a (roughly) ten step process to define who we were, build confidence in the new “us,” change and launch several new products, and launch our new brand out into the world. Part 1 of this newsletter will cover the first 5 steps. Part 2 will cover the last 5 and lessons learned.

Positioning statement exercise

Experimentation

Alignment aka the fight for Membership

Personality exercise

The Promise vs. The Proof

Building the visual identity and brand guidelines

Eye-popping assets

Firing up the PR machine

Hiding in plain sight

Launch day & measurement

Positioning Statement Exercise

The first step in our rebrand was to align the leadership team on our positioning: who were we, what was our unique differentiator, and why would anyone care?

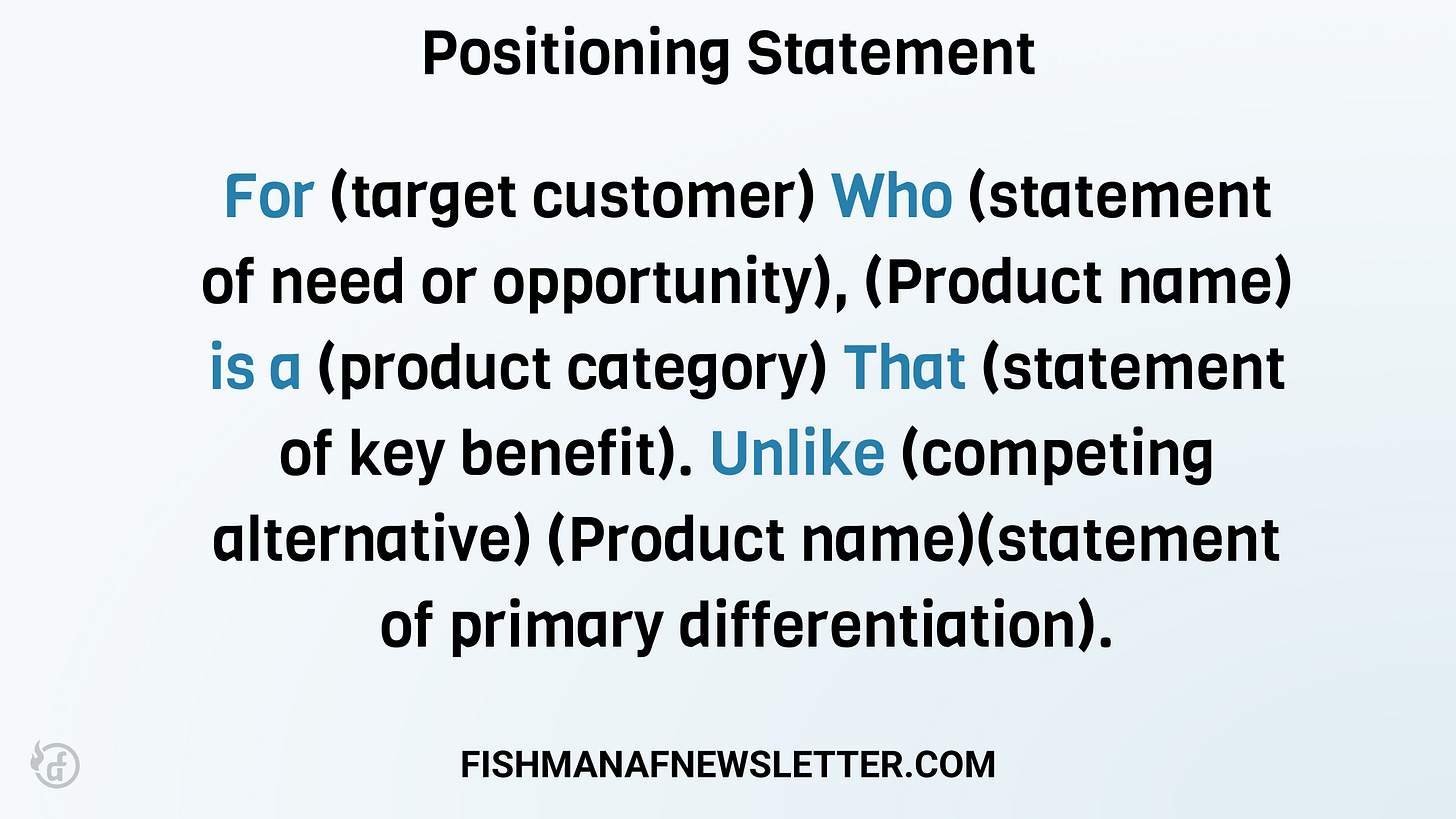

To help guide us we enrolled the temporary services of Arielle Jackson (she’s got an amazing branding course on Maven). For someone who didn’t know how to start (me) she was hugely helpful and the right facilitator for us. She took us through a process that I jokingly refer to as “Positioning Mad Libs.” It’s a simple and powerful framework based on this statement:

For (target customer) Who (statement of need or opportunity), (Product name) is a (product category) That (statement of key benefit). Unlike (competing alternative) (Product name)(statement of primary differentiation).

She provides a lot more detail on this in a fantastic First Round Review article.

From Arielle:

I catch myself sometimes disparagingly referring to that positioning framework as Mad Libs too, but then I explain that there is a big difference: with Mad Libs what you put into each blank space is totally independent — and part of what makes the whole thing funny. With a positioning statement, each blank space reflects an important decision and dictates what’s in the other blank spaces. For example, once you narrow in on your audience, the competing alternative becomes clear. It’s not just randomly picking stuff and putting it all together. It has to reflect and summarize a bunch of strategic decisions. Start with your audience and their problem / what they are doing today. Then define what you’re up against and understand the existing categories in your space and where you might play. Then clarify what you’d want a happy user of your product to say about you when you’re not there (your benefit) and a reason to believe that benefit, usually something about how your product works, that sets you apart from the competing alternative (your differentiator).

Several years later I realized that this framework is quite close to the Use Case Map framework I teach at Reforge.

We worked through the positioning exercise in a series of workshops. Locked in a room with a handful of the leadership team and Arielle wrangling us and directing our energy.

Here is the exact document we used at Patreon to go through these workshops:

The most difficult part of this process was three-fold.

First, we started with over 30 different opinions on our statement of purpose – or why we were needed in the world. Here’s the evidence:

This was challenging because our product, in fact, did do quite a lot for creators BUT it was important to break that down into one, distinct key benefit. This forced the hard conversation around why we existed in the first place – to turn the love from your biggest fans into money.

Second, we struggled with defining our category. Businesses can approach this in two ways: create a new category (home wifi system) or align with an existing category (fan club). Creating a new category is really difficult because you have to educate the masses about what your category is. This is why, when Patreon launched, it anchored itself to Kickstarter and positioned itself as “recurring crowdfunding.” People were already familiar with Kickstarter and this was an ongoing way to do that.

We were trying to cram community, engagement, fans, status, and about a million other concepts into one category. It wouldn’t work. Here’s the evidence:

We ended this phase of the project with two potential categories: a fan community OR a membership platform. In Step 3 I’ll talk about the fight for alignment and the eventual decision to go with Membership Platform.

Third, we had a really challenging time defining our primary differentiating factor. This came down to a decision between two opposing statements: are we for doing what you’re already doing and monetizing that OR did we want to say that Patreon required some new work but the return was tremendous. Jack was a firm believer in “do what you're already doing” but we knew that creators found that wasn’t typically true. We also knew that half of a creator's fans would pay for “what you’re already doing” but the other half was interested in “more stuff.”

Ultimately went with “extra work” because it was more true to the experience of using Patreon AND we knew from our conversations with creators that the idea of a value exchange would land better with them.

Our final positioning statement:

Arielle had this to say about the project:

When I started working with Adam and the Patreon team, Patreon was seen as a tip jar both by the creatives who used it and their fans. This was 2016, before ‘creator economy’ was a term, and before we had all of the subscriptions we do today. It was clear that the most successful creators on the platform and their biggest fans were using it more for premium content subscription and less as a tip jar. That’s where the company was going. So we repositioned the company to reflect that membership model. You didn’t throw in a few bucks to support an artist or musician whose work you liked; you subscribed to them and through that got access to exclusive content and experiences. Today it sounds obvious — a lot of positioning does in hindsight! — but in 2016 that was a big shift for the company and it was great working with the team to help them articulate it.

Experimentation

So our leadership team was all aligned (or close to it; more on that in the next section). But the scientist in me needed proof. With Growth work I run experiments but you can’t experiment with a brand launch. It takes too much effort to create a new brand and Patreon couldn’t do all that work and then decide it was the wrong move and reverse it. Not a chance.

But I still needed that proof. So I did find a way to experiment.

We did this both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Qualitative

The first research and experimentation we did was to develop a better qualitative understanding of how creators in our target (creators with established followings who regularly post online) would respond to some statements about the “new” Patreon.

We had to do this in a way where existing knowledge of Patreon wouldn’t bias the results so we hired a 3rd party researcher to help us recruit participants and run a brand-blind study using old and new language to describe the platform. After describing two different companies we asked participants which one they’d prefer being a part of.

The results were conclusive: the new language won.

Quantitative

We weren’t comfortable with only running a qualitative study so our next set of research and experimentation around the language that we used on our site. This enabled us to reach far more prospective creators at scale than via one on one interviews.

We created an A/B test that scrubbed the site of all “crowdfunding” language and replaced it with “membership” language. Of course we used the experiment template I wrote about a few weeks ago. We were measuring the impact on creator launches and earnings (remember, this rebrand was all about creator perception). The language change had a subtle but positive impact on launches and earnings.

Armed with this information we were ready to proceed… or so I thought.

Alignment (aka The Fight for Membership)

We had one, not-so-small problem that emerged: Jack was having second thoughts about how we would describe our category. Specifically the “membership platform” language. His concern, a valid one, was that it didn’t include anything about a creator’s fan community – a topic that Jack is quite passionate about (see also: every video that Jack has ever made).

At the start of the entire project Jack had asked the executive team who the decision maker was on this project. I said it should be Jack since he was the co-founder and CEO and he understood the creator audience best. Jack disagreed. He wanted it to be me and said that when we reached critical blockers in the project I would have the final say. Everyone said that if necessary they would disagree and commit to my final decision.

So fast forward to the decision around the Membership Platform category language. I did what any “decider” would do – I barricaded myself, Jack, our brand/copywriter (Taryn), and our head of communications (Mollie) in the hottest, least ventilated conference room I could find and said we weren’t leaving without a decision.

The debate was impassioned – Taryn argued the case for Fan Club, but Jack was vehemently against it. I doubled down on Membership Platform using the evidence we had gathered from the qual and quant research and experimentation. Things got a little weird (probably because of the heat) and we started to riff on combinations of fan community and membership platform (nope). And finally, after hours of conversation, although Jack still weakly disagreed with Membership Platform I got him to commit.

We were all aligned and the process could continue!

Personality Exercise

In parallel to the great membership platform category debate I was also working on the “personality” of our brand with Taryn.

In this exercise our goal was to identify our voice and the personified version of our brand – how we’d sound and who we’d be if you bumped into us at a bar.

We identified the brand attributes that mattered most to us using a “this, not that” framework, the persona (who is this Patreon character), how we’d write our words, and words/punctuation we like and don’t like.

Here’s how our personality ended up:

Fearless and witty, imagine your somewhat odd college roommate 10 years later. Dressed in jeans and well-worn black Converse, he’s pulled it all together and channeled his intense energy into something useful. A little bit Dave Eggers, a little bit Pharrell, he’s now a producer at NPR who’s passionate about making sure teens get exposure to the arts. On the side, he runs a small non-profit studio that provides art and music instruction to kids at schools where budget for the arts has been cut. When you run into him, he has stories for days but acts like it’s not a big deal and cares way more about what you’ve been up to.

And the final Patreon Voice document:

The Promise vs. The Proof

You might think that the hardest steps of this process were behind us. Unfortunately (for me) this couldn’t be further from the truth. Throughout all of this work I was keeping the company informed through regular updates and communication – I talked about the project, our positioning statement, and got feedback on all of it from team members.

Throughout that process I started hearing an underlying rumbling that rebranding the company was going to be 1) Ineffective and 2) A lot of work for little return.

The “ineffective” crowd was making good points. We were changing our look and feel but the underlying product wasn’t going to change.

And I agreed: if the brand is the promise you make to your customers then the product experience is the proof, or the delivery of the promise. We were going to make a new promise without backing it up and that was problematic.

If we wanted “Membership” to land effectively then you had to feel like something significant had changed at Patreon. So in order to achieve that we broke ground on four major initiatives – creator tools that demonstrated “membership” and not “crowdfunding.”

A new Patreon-exclusive mobile experience called Lens (eventually folded into the Patreon app)

An early access functionality for releasing exclusive content to patrons then making it available more widely later

Gated livestreaming functionality (another membership benefit)

Membership tooling called Patron Relationship Manager (PRM for short)

We were building these proof points alongside development of the new brand and needed everything to land at the same time to be successful. As you can imagine, deadline-driven product development put me on a lot of peoples’ shit lists. But every so often it needs to happen.

So that’s the first half of the rebranding journey. We covered:

How to create your positioning statement

How to experiment to validate brand work

Getting alignment with your founder/CEO

How to build a brand personality

Creating both the promise and the proof

In the second part of this series I’ll cover how we pulled all of this off and launched with nearly zero issues. Plus how to ignore all the inevitable haters of the new look and feel.

I’ll cover:

Building the visual identity and brand guidelines

Creating eye-popping assets

How to fire up the PR machine

Hiding in plain sight aka how we built and launched with zero issues

Launch day & measurement

Some of the valuable lessons I learned from this first part of the process:

Your positioning statement is the glue that holds everything together and aligns the company around what you stand for. Don’t skimp on the effort required here.

You CAN experiment with brand work.

Make sure you’re on the same page about who has the final decision. Just when you think you’ve got alignment you probably don’t.

Your brand personality tells the world who you’d be if someone bumped into your brand at a bar.

Changing the brand in a vacuum won’t work; you’ve got to deliver the proof points in the product as well.

This does a very good job summarizing a complex decision process: "invest in improving your brand when your brand perception is getting in the way of growth"

Great content and story Adam, it's very helpful. Also thanks for sharing the positioning workshop and the voice (aka personality) document. I will steal it ;)

I like how Patreon took the time and did proper research for understanding why growth was slowing. It would be easy to jump to conclusions and think that Patreon just misses some specific features. Finding out the real problem was not so obvious to figure out.

I was also wondering if you guys where hiring employees based on the personality voice (witty, fearless, and inviting)?

You also give a great example of how to both use qualitiative and quantitative data to validate the hypothesis about what the root cause is and how it might be solved.

Looking forward to the next article :)